The world wants to master the process of corralling carbon, and Occidental Petroleum Corp. is building a futuristic machine on the dusty plains of Texas designed to do just that.

The billion-dollar complex, called Stratos, will suck carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and bury it deep underground. Amazon.com Inc., Shopify Inc., Airbus SE and the Houston Texans football team are among the businesses signed up to pay by the ton for captured carbon, long before the site is operational. US President Joe Biden is putting hundreds of millions of dollars behind the technology. Occidental Chief Executive Officer Vicki Hollub has spent $1.1 billion buying the startup behind Stratos and, after successfully lobbying for government support, intends to build 100 plants just like it. Warren Buffett, Occidental’s biggest investor, has given his tacit blessing.

This is not the first time Occidental has bet big on technology to manage carbon. A mega-plant for carbon capture and storage — a facility named Century located about 100 miles from Stratos — was built by the oil giant in 2010. At the time it was set to become the biggest-ever example of carbon capture, representing more than 20% of global capacity.

Unlike the newer technology used in Stratos, known as direct air capture (DAC), Century pulls CO2 from a dedicated source of emissions: It’s built into a natural gas processing plant. That older process is both better established and much cheaper than the newer machines built to suck CO2 from the air. There’s also the added advantage of a more direct business application, with Oxy deploying recovered CO2 from the gas plant as a tool to produce even more oil. But that older facility — with simpler tech and a production-linked incentive — has consistently failed to deliver results.

A Bloomberg Green investigation has revealed that Century never operated at more than a third of its capacity in the 13 years it’s been running. The technology worked but the economics didn’t hold up because of limited gas supplied from a nearby field, leading to disuse and eventual divestment. Oxy quietly sold off the project last year for a fraction of the build cost. It was a far cry from the fanfare the company made in the plant’s early years — and the anticipation that’s been building for Stratos.

Occidental said the Century plant “continues to operate as designed.” A spokesperson said in an email it would be a “mischaracterization” and “false narrative” to use the plant as an example of CCS project performance.

Shortcomings have marred virtually all of carbon capture’s previous generation used for climate purposes, an assortment of a few dozen facilities around the world grouped under the acronym CCS (for carbon capture and storage). Century’s struggles show the risk of underwriting the cost of carbon capture with fossil fuel revenues. Even if the technology works, projects frequently fail when commodity prices drop.

This legacy of underperformance is a warning about relying on the next wave of carbon-wrangling tech — both newer DAC projects like Stratos and an anticipated build-out of CCS facilities like Century on a vast scale — to play the role of climate savior. Both technologies, new and old, are now being presented as ready-to-go climate solutions, in particular by the oil sector which is eyeing them as a licence to operate.

The path forward from here, according to the International Energy Agency, requires rapidly scaling up CCS worldwide. That means adding more than one Century-sized plant each month through the end of the decade, because it’s cheaper than using newer carbon-removal technologies and stops emissions from entering the atmosphere in the first place. Focusing attention on CCS and enlisting the global oil industry’s support have become an emphasis of the upcoming COP28 climate summit, with oil exporter United Arab Emirates playing host. As mid-century net-zero goals get closer, researchers anticipate vastly expanding DAC projects to draw down CO2 and keep temperatures in line with the Paris Agreement.

Malte Meinshausen, professor in climate science at the University of Melbourne and author of a landmark report on the topic from the United Nations-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, is among those who believe we “absolutely need” carbon capture “in order to get to the lower levels of climate change we want to get to.” Like many climate-focused observers, he’s worried about just who has been empowered to handle much of the deployment.

“The problem,” Meinshausen said, “is that it has the wrong bedfellow in the fossil-fuel industry.”

The oil sector’s obsession with carbon capture has deep roots that long precede the current climate crossroads. Technology to separate CO2 from other gases dates back to the 1930s, and since the 1970s it’s been a tool in the production of oil. The last dregs in ageing fields can be sticky and need some form of lubricant. Pure CO2 is perfect for this role and became the lube of choice in a process known as enhanced oil recovery.

After decades of deployment, however, total carbon capture capacity globally is only about 45 million tons of CO2 per year. That’s just 4% of carbon capture needed by 2030 to be on track for net zero by 2050, according to the IEA. And beyond the usefulness of producing more oil, the technology has also been the beneficiary of a decade of policy incentives, including new laws from the US government to increasingly subsidize the burying of CO2. Now companies can get as much as $85 per ton.

Why hasn’t carbon capture become a more mainstream technology? To answer that question it helps to look back at Century’s shortcomings.

Capturing Carbon: Faltering Present, Big Future

- A Startup Battles Big Oil for the $1 Trillion Future of Carbon Cleanup

- Big Oil’s Climate Fix Is Running Out of Time to Prove Itself

- Ground Zero in the Fight Over Carbon Capture Pipelines

When Hollub was managing Oxy’s enhanced oil recovery in the Permian, she came to realize that the greatest limitation wasn’t the amount of oil in the ground but the availability of CO2. Most of the company’s supply comes from mining the gas underground, and its fields had started to run low. That same worry features prominently in the company’s shareholder disclosures to this day. Without an ample supply of CO2 at hand, yield from some of fields would disappoint.

Century began to take shape in 2008 as a potential solution to this problem. Oxy announced plans to build the plant and accompanying pipeline infrastructure in partnership with SandRidge Energy Inc., another oil and gas company. The facility was designed to separate naturally existing carbon dioxide that was mixed with natural gas supplied from the nearby Pinon field.

The gas mixture entering the plant is brought to high pressure, cooled and then treated with chemicals to separate out the CO2. Oxy got to use the CO2 to help produce more fossil fuel while SandRidge got to sell the pure natural gas.

Ray Irani, Oxy’s then-CEO, expected Century to help increase the company’s Permian Basin production by 25% to about 225,000 barrels of oil equivalent a day. It would become the world’s biggest carbon capture plant, capable of processing 8.4 million tons of CO2 every year.

“Any capital-intensive project like this is not for the faint of heart,” said Todd Stevens, a former senior Oxy executive who was responsible for the deal with SandRidge. “You find out over years if you were successful.”

Century wasn’t. It never reached the projected levels of CO2 capture. From 2018 to 2022, Century captured less than 800,000 tons of CO2 each year, according to an exclusive analysis of US Environmental Protection Agency filings conducted by Data Desk, a consultancy that focuses on polluting industries. That’s less than 10% of the plant’s nameplate capacity. (Oxy didn’t comment on these figures.)

Century was built with two engines, referred to as “trains” by workers at the plant. One is capable of catching 5 million tons of CO2 and the other can handle 3.4 million tons. But only one ever ran and never at more than half its capacity, according to a former employee who asked not to be named for fear of repercussions. Recent analysis of satellite images by Data Desk shows that the cooling towers on the second train are idle, indicating it’s not in operation.

In January 2022, following a decade of struggles at the project, Oxy quietly rid itself of the asset. The sale to a subsidiary of oil magnate Malone Mitchell’s Mitchell Group was not publicly announced by Oxy before being published on a no-name basis in its annual report. Oxy secured around $200 million after investing more than four times as much in construction alone.

A company spokesperson said Occidental continues to “take and utilize all of the CO2 captured” at the Century plant and has a long-term commitment to do so. Representatives of Mitchell Group did not respond to a request for comment.

For Steven Feit, senior attorney at the nonprofit Center for International Environmental Law, Century’s disappointment should serve as a warning to those pinning hopes on the technology to help avert catastrophic climate change. “The history of carbon capture,” he said, “is one of over-promising and under-delivering.”

Unlike hiccups at other carbon capture plants, Century’s failings appear to come down to economics rather than technological issues. Almost as soon as the Century project was announced, natural gas prices plummeted and eventually fell by more than 70% over the following 12 months. Prices hovered around that trough for much of the next decade, torching the economics of drilling wells in the Pinon field. SandRidge fell short on its contracted gas delivery. The company did not respond to a request for comment.

“We just didn’t have the gas feedstock to support the plant,” said Paul Kindsfather, an operator at Century until he left Oxy in 2013. The oil company eventually acquired the field itself in 2016 but failed to revive production, dooming its supersized carbon capture plant to remain mostly dormant.

Century now finds itself on a growing list of CCS projects that failed to live up to lofty expectations. Decades of failed projects indicate controlling carbon is far more temperamental than backers let on.

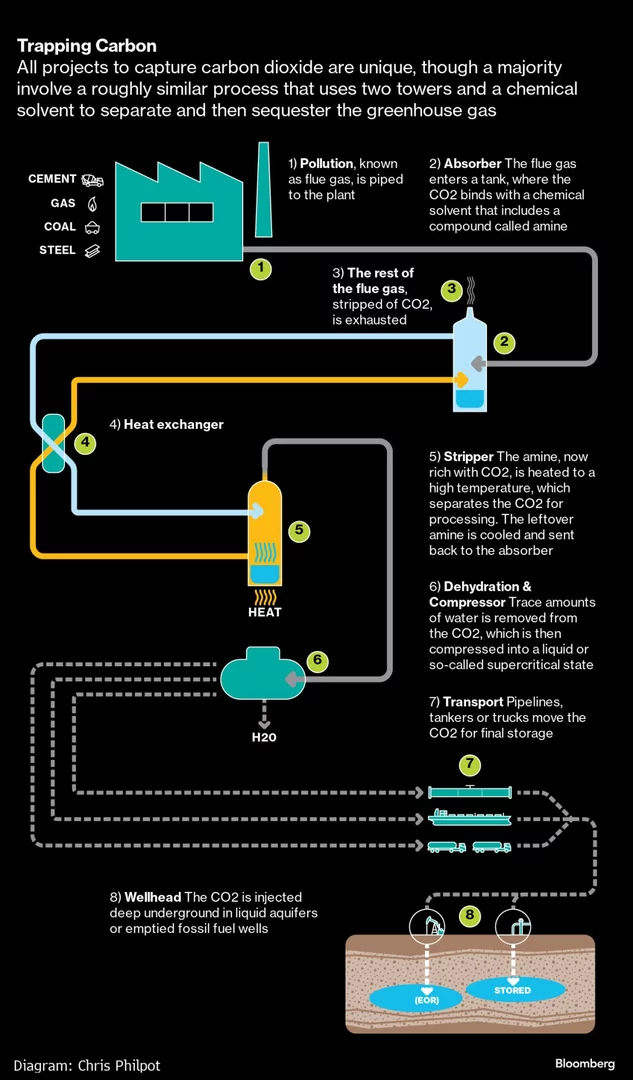

Capturing carbon is typically an eight-step process from production of CO2 to burial. At each stage, there’s a potential pitfall. The mixture of gases will be different based on whether the emissions being captured come from processing natural gas, a power plant that burns coal, a cement factory or the open atmosphere. At the end of the line, assuming no problems in collecting CO2, there will be wide variations in geology where the planet-warming needs to be sunk. It’s not just the equipment that must work in sync every step of the way but also the business case for operating at all — something that’s often balanced across several different companies.

Examples of misfires abound in the previous generation of CCS. In Mississippi, a much-heralded "clean coal" project at Southern Co.'s Kemper power plant ended up scrapped due to technical problems as costs blew up to $7.5 billion. Chevron Corp. has consistently failed to run its Gorgon CCS plant in Australia as expected after seven years and $2.1 billion invested due to engineering problems around sinking the CO2.

It might seem, from a climate perspective, like a boon that Century never reached its full potential since its performance was inextricably linked to natural gas production. But picking the wrong location for an expensive carbon capture project carried real climate costs. Cheaper shale gas elsewhere met the same demand, without the benefit of carbon capture. As a result, total emissions likely ended up higher.

That’s the risk of tying a technology with possible climate benefits to the production of fossil fuel. When commodity prices go awry, carbon capture can end up suffering. This pattern has played out elsewhere. Oil prices cratered during the pandemic, for example, prompting Exxon Mobil Corp. to delay a marquee CCS project in Wyoming. Another called Petra Nova connected to a coal power plant near Houston also shut down for a time as prices dropped.

CCS is “a mature technology that's failed,” said Bruce Robertson, an energy finance analyst who has studied the top projects globally. “Companies are spending billions of dollars on these plants and they're not working to their metrics.”

It’s unlikely that Occidental’s direct air capture ventures will face the same supply issue as Century. After all, carbon dioxide is everywhere. But there are still nagging similarities.

These next-generation plants for capturing carbon will rely on a complex process that requires both the technology and the economics to align to be a success. Unlike traditional carbon capture from a power plant or industry, DAC’s tech and business models are immature.

Complexity is one reason why the cost of capturing carbon hasn’t seen the type of declining prices that have characterized the globe-spanning spread of renewable energy in the past decade. In the case of solar panels or even wind turbines, companies have to make thousands or millions of the same units. And the more units they make, the more efficient they get.

But unlike solar or wind farms, each CCS plant is close to unique, which means learning to make the next one cheaper is much harder. That’s why after 50 years of deployment the technology’s costs haven't fallen all that much. Oxy’s DAC moonshot at Stratos is even more expensive than the CCS technology it deployed at Century. Pulling carbon from the air is “much bigger and there’s more challenges,” said Kindsfather. “It’s not cost or resource effective right now.”

Despite a 50% rise in atmospheric CO2 since pre-industrial times, the planet-warming gas makes up only 0.04% of ambient air. That’s about 1,000 times more dilute than in the stream available to the Century plant. The lower the concentration of CO2, the more energy a plant must expend in separating it.

That’s why the cost of trapping CO2 from the air, according to Oxy’s estimates, is more than $400 a ton today compared to less than $60 a ton needed to capture emissions from a coal power plant or a natural gas processing facility like Century. Hollub says costs for the newer technology will come down over time as Oxy learns and builds more.

But such is Oxy’s enthusiasm for the unproven technology that it has pledged to go on a DAC spree. The company has sold carbon removal services before even breaking ground on Stratos, thanks to a mix of government and corporate support. Airbus, for example, has booked itself 400,000 tons of carbon dioxide removed from the air — roughly 20% of the plant's planned capacity over the first four years of operation.

A growing number of companies are willing to pay high prices for carbon removal credits. This trend is being fueled in part by the ongoing backlash against dirt-cheap offsets that have a minimal impact on reducing emissions. As more companies get serious about net zero and seek to avoid greenwashing, there’s an expectation that the market for carbon removal credits could reach hundreds of billions of dollars. But it remains far too early to say if that will prove to be the case.

Crucially, DAC plants are also core to Oxy’s plans to boost its oil and gas production, which Hollub says will be marketed as “net zero” by coupling it with carbon removal. “We will continue to actually grow our oil and gas production,” Hollub said in an interview with Bloomberg Green’s Zero podcast. “But we'll grow it in a way that gives us the opportunity to generate net-zero oil.” She described burying CO2 without using it to produce more oil as “a waste of a valuable product.”

Oxy has the distinction of being the first US oil major to lay out an ambition to become fully net zero by 2050, including emissions from customers who buy its oil and gas. That puts the company ahead of US peers like Exxon, Chevron and ConocoPhillips. But Hollub’s ambition raises concern among environmentalists and policymakers, including officials from 17 countries and the European Union who recently warned against using CCS to justify new fossil fuel projects.

Oxy is embracing these technologies “as a license to operate,” warns Glen Peters, senior researcher at the CICERO Centre for International Climate Research and another IPCC author. “There is no scenario that exists where you continue producing oil and clean up” with carbon removal.

Carbon capture has been used by the oil sector to claim it’s working toward a net-zero future, and DAC is offering a new twist on the industry’s sustainability claims. But the failures at Century and other CCS plants serve as a warning of counting on the technology to come through — and the ends to which it will be used.

Even if new projects are deployed properly, it’s “no panacea,” said Meinshausen. “The high cost of the technology makes it very clear that avoiding the emissions in the first place is economically the wisest thing to do.”

--With assistance from Jeremy Diamond.

Author: Natasha White, Akshat Rathi and Kevin Crowley