Scientists have worked out how close a neutron star collision would have to be to threaten all life on Earth, in a not-remotely-terrifying new study.

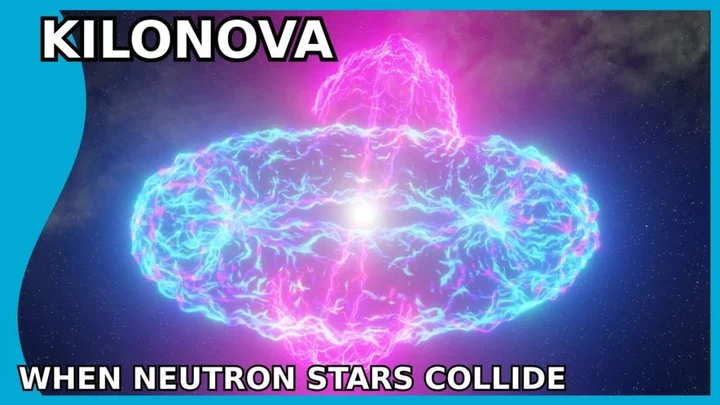

The event, known as a kilonova, is among the most powerful and explosive in the known universe. It’s not quite as bright as a supernova – but we should still keep our distance.

Haille Perkins, team leader and a scientist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, told Space.com: “We found that if a neutron star merger were to occur within around 36 light-years of Earth, the resulting radiation could cause an extinction-level event.”

That’s about 212 trillion miles – which seems like quite a large danger zone. But we need not worry, apparently.

Kilonovae are extremely rare and difficult to spot, because they happen so quickly. Scientists, including those from the University of Warwick, recently managed to observe one by using the James Webb telescope.

The explosion first produces a blast of gamma rays which lasts for just seconds. If we got caught in one of those, it would fry us all rather quickly. That’s pretty unlikely because they go in two thin lines out from the centre of the blast.

They also cause an afterglow of X-ray emissions in the surrounding dust and particles. If we’re within 16.3 light years of those, we’d be in trouble.

But the worst bit is the cosmic rays (of course!) – energetic charged particles spreading out from the explosion in a bubble.

If these hit Earth, they would strip the ozone layer and leave us vulnerable to ultraviolet rays for several thousand years. That would be a bummer because, again, we’d all die.

Fortunately, kilonovae are so rare that we’re more likely to get hit by an asteroid, added Perkins.

She said: “There are several other more common events like solar flares, asteroid impacts, and supernova explosions that have a better chance of being harmful.”

That’s good then.

New kilonova discoveries

In the most recent kilonova, it was the gamma rays that alerted the astronomers to the fact something big was going down.

Then, they got in touch with various telescopes and detectors to ask them to focus on the bit of the sky where the burst had come from, and bingo: kilonova.

Here's what it looked like on the JWT's feed.

One of the major discoveries from this one is that kilonovae produce an element called tellurium, a relatively rare element on Earth.

They also worked out where the two neutron stars came from: a spiral galaxy about 120,000 light years away from the location of the final explosion.

That’s about the diameter of the Milky Way, and just a little further away than the mere 36 light year danger zone, then. But it’s food for thought nonetheless, eh?

How to join the indy100's free WhatsApp channel

Sign up to our free indy100 weekly newsletter

Have your say in our news democracy. Click the upvote icon at the top of the page to help raise this article through the indy100 rankings.